Waldorf News

Einstein May Never Have Used Flashcards, But He Probably Built Forts: Bringing play back into the lives of children

By LORY HOUGH

In some ways, this headline is almost funny, the idea of a young Einstein, wild hair flying, throwing his mother’s quilt over a couple of chairs and crawling underneath.

But to Elizabeth Goodenough, M.A.T.’71, a headline like this is not a joke. We’re a busy-by-design society that’s become so concerned with turning kids into baby Einsteins that something critical to childhood, something that Goodenough holds sacred, is fast becoming extinct: free play.

She says that all you have to do is drive around American cities and towns to see for yourself; there are very few kids outside.

This is why Goodenough raised money to start a project called Where Do the Children Play? which includes a PBS documentary that will air in the fall, as well as a companion book and website. In addition, with a coalition of national children’s organizations, she hopes to start a national dialogue about the issue. The project, which grew out of her earlier book called Secret Spaces of Childhood, is aimed at raising public awareness about the critical importance of play. Beyond the obvious — play helps kids stay in shape — it also promotes creativity and teaches skills such as negotiating and how to be around others.

“Play takes many forms. It may be best defined from within as a spontaneous human expression that relies on imagination and a sense of freedom,” Goodenough says. “Players invent alternative contexts for conversation, visualization, movement, and interaction with real objects. They discover release and engagement, stimulation, and peace. Although play can arise anywhere, even in a cement cell, children are naturally beckoned by the living world to enjoy perception and the sensations of being alive.”

And Goodenough, a lecturer in comparative literature at the University of Michigan, isn’t alone in understanding the importance of this. The headlines calling for more play and less structure are endless. There are also a small but growing number of child development experts, medical researchers, space planners, and other educators focusing on this issue in an attempt to keep play from slipping even further from the lives of children.

How We Got Here

It’s probably not a surprise to anyone that one of the biggest factors in the loss of free play has to do with parents being programmed by the ever-expanding “baby educating industry” into thinking that in order to survive in today’s global economy, kids need to be better, brighter, and busier than ever before.

“It’s a competitive foot race from the womb, this sense that you’ll miss out,” Goodenough says. “Adults have picked up the pace so quickly. What’s next? What’s next? What’s next?”

“It’s a competitive foot race from the womb, this sense that you’ll miss out,” Goodenough says. “Adults have picked up the pace so quickly. What’s next? What’s next? What’s next?”

In an age where we clearly know more about how brains operate and how humans function, parents take parenting seriously. As a 2001 article in The Atlantic Monthly stated, “Your child is the most important extra-credit arts project you will ever undertake.” As a result, by the time these baby wonders reach college, they’ve become goal-oriented, resume-building “organization kids” who “work their laptops to the bone.”

What adults need to understand, writes Michael Meyerhoff, Ed.M.’75, Ed.D.’84, in his booklet The Power of Play, is that free play isn’t a waste of time — it actually helps children learn.

“It is clear that young children who explore, investigate, and experiment through play build strong foundations in every important area of development, including intelligence, language, social competence and emotional security,” he writes.

As Professor Paul Harris recently told the French publication L’Infobourg, “The child’s capacity to pretend and imagine is not a symptom of immaturity or absence of logic. Rather, it forms the foundation for a more mature mode of thought toward another’s point of view.”

To be fair, parents aren’t solely to blame. Gone are the pre-cable TV days when all you got were four or five stations. Today, the lure of satellite and cable TV is strong. (One recent survey found that 69 percent of American kids ages 6 to 14 had TVs in their bedrooms.) Add the Internet, TiVo, and video games and most kids don’t feel the need to play, especially outside. Other factors include sprawl, which has taken away the woods and open areas in many neighborhoods. Fear of violence also means many parents no longer open the back door on a nice day and tell their kids to come home when it gets dark. (In the last 25 years, the average “home range” for suburban kids, in fact, shrank from one mile to less than 550 yards.) Working parents are also crunched for free time.

“Parents are working longer hours so children aren’t getting the outdoor time,” Goodenough says. “Even if there are outdoor sports, it’s not the same as that deep connection to the earth. It’s not about the outdoor world.”

No Time Out

This connection to the earth is critical, says Goodenough. Play can certainly happen indoors — young Einstein building the fort out of his mother’s quilt, for instance — but outdoor memories are what really stick.

“Research has shown that outdoor play takes a far bigger role in people’s memory than indoor play time, even if hours outside are fewer than those within,” she says.

“Research has shown that outdoor play takes a far bigger role in people’s memory than indoor play time, even if hours outside are fewer than those within,” she says.

This is especially relevant today: kids are shuttled back and forth all day in cars.

“So often they don’t travel on foot,” Goodenough says, discussing missed opportunities for children to use all of their senses. “They’re driven everywhere in SUVs.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Kids Walk-to-School: Then and Now — Barrier and Solutions, 42 percent of children ages 5 to 18 walked or bicycled to school in 1969. By 2001, the number dropped to 16 percent. Reasons cited include families living further from schools that are increasingly being built on large parcels on the outskirts of town, traffic concerns, and the fear of crime.

“No one wants to have their kids shot or kidnapped,” Goodenough acknowledges, but “that’s actually a declining risk in the last decade.”

Still, she says, “Kids spend too much time now indoors, especially at school.”

In fact, some schools nationwide are doing away with recess altogether. According to the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education, more than 40 percent of elementary schools nationwide have reduced, eliminated, or are in the process of eliminating recess from the school day.

“It shows the atrophy of adults who don’t know how to enjoy time or the outdoors, especially with children,” says Goodenough. “What started as a survival skill — building shelters and going out into the world — doesn’t exist anymore. Everything we do now is many times removed from the natural world. That’s why some kids say they’d rather be indoors where the [power] outlets are.”

For some kids, their only outdoor time is spent at local playgrounds, what Goodenough calls “austere concrete and plastic gyms.” Usually there’s a climbing object and a swing, all on a flat surface. The problem, she says, is that this kind of space only develops gross motor skills like balance and coordination. It does little for creativity and sensory exploration.

This focus on the physical goes back a long way. Author Susan Solomon, a contributor to Where Do the Children Play?, writes in American Playground that when freestanding playgrounds were first created in the late 1880s, one of the beliefs was that “physical activity, especially muscle control, had a moral dimension that would create better citizens.”

Eventually playgrounds got dulled down even more as safety concerns grew. In 1999, 156,000 children were treated in hospital emergency rooms because of public playground-related injuries, according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Add to this a lawsuit-crazy culture and public playground design has become an exercise in restraint and caution.

Goodenough says that in Ann Arbor, Mich., where she now lives, sledding was recently banned during recess after an elementary school student suffered a concussion. Concerns over bullying and the lack of personnel to supervise students have also prompted schools to put limitations on playground use.

Goodenough says that in Ann Arbor, Mich., where she now lives, sledding was recently banned during recess after an elementary school student suffered a concussion. Concerns over bullying and the lack of personnel to supervise students have also prompted schools to put limitations on playground use.

Of course, not all cities and towns are doing away with recess, and some are starting to understand the importance of free play. Even New York City, a haven of traditional playgrounds, is creating new “playscapes” that encourage exploration and imagination. Based on child development theories, the new spaces will include trained “play workers,” water features, ramps, and open-ended objects.

“Play is not an option for kids; play is how children learn to build community, how they learn to work with other people; it’s how they learn to kind of engage their sense of creativity,” the playscape designer, David Rockwell, told The New York Times in January. “We’re thinking of imagination as important a muscle as running.”

How She Got Here and Where We’re Going

Goodenough’s interest in all of this was sparked in 1990 when she was teaching in California and pregnant with her second son, Will. During a lecture one day by environmental psychologist Roger Hart about children’s relationships with the environment, she started thinking about what motivated children to find secret hiding spaces, what she calls “just for me” places.

“There’s an unforgettable thrill of being apart from the rest of the world,” Goodenough says. “It can be modest — hiding in a cupboard or under a chair — but that capacity to be able to look out and not be seen is very powerful.”

Six years later, while on vacation at Pocono Lake in Pennsylvania, without toys or a TV, she and Will spent an afternoon building little huts out of ferns and bark. She started thinking again about secret spaces. Through teaching children’s classics and after talking to other people about their memories of childhood, she decided to pull together a collection of essays, poems, and short stories, called Secret Spaces of Childhood. Joyce Carol Oates and Robert Coles were two of the contributors. She says she was surprised at how varied the pieces were.

“I thought everyone would have the same memory — the blanket over the table or the tree house, but they were all different,” she says. “It’s about developing a sense that’s as unique as we are. What concerns me is that when you take away the choice — you give a child a toy with a single monologue that’s pulled by a string — you take away imagination.”

Luckily, she says her own childhood in Grosse Pointe Farms, Mich., was full of imagination, thanks in part to the woods behind the house and a family ethos that cherished the outdoors.

“In our family, if you were taking a walk or watching the stars at night, this was considered sacred space,” she says.

As we continue to lose this sense of sacred space, and along with it, free play, Goodenough says it’s a downward spiral for children, documented by research: a rise in stress, diabetes, and obesity, for starters. Children also lose an appreciation for the environment and the opportunity to “find their niche.”

“In our highly programmed, commercial world, down time and away space slip away. Children need the space and time every day to do nothing, so that who they are can grow.”

To learn more go to www.childrenplay.org.

This article by Lory Hough originally appeared in the Harvard Graduate School of Education newsletter. To view the article at source, click here.

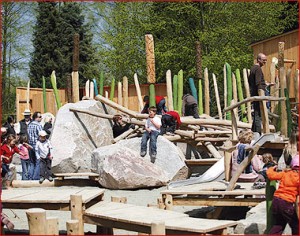

The first two photos are of boring playground equipment and a bored child. The next two images are playgrounds built by Kukuk from Stuttgart, Germany. Kukuk has helped many Waldorf schools create vital playspaces. Visit them here.

Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Waldorf Stories for Everyone

Waldorf Stories for Everyone Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Waldorf Training in Australia

Waldorf Training in Australia Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Preparing Teachers for 2024-25 Grades 1-8

Preparing Teachers for 2024-25 Grades 1-8 Training in Traumatology & Artistic Therapies

Training in Traumatology & Artistic Therapies Grade-specific web courses for teachers

Grade-specific web courses for teachers Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds