Waldorf News

From Cursive to Cursor: The Death of Handwriting by Merry Gordon

Editor’s note: As I was preparing this article, I couldn’t help but remember when my son took the SAT a few years ago. The hand-written essay had just been reintroduced and there was a collective moan that went up in the room as the students all complained that they never wrote anything with a pencil anymore. I don’t think the Waldorf students were moaning that morning. -DK

You might have called it longhand, or Spencerian script, or Palmer penmanship. Whatever you remember it as, the graceful loops and whirls of your childhood may be a thing of the past for today’s grade schoolers. Can’t believe that your kid might know script only as a font style? Believe it: in the ever-changing and increasingly technocentric world of public education, penmanship is passé.

When the SAT required a handwritten essay section a few years ago, many thought that cursive might see a revival, but by 2007 85% of test-takers were responding to their prompts in print. If cursive is seen as irrelevant in high-stakes testing, our data-driven schools seem likely to abandon it altogether within the next few years.

The reasons for this are logical. Cursive served a practical need once—over one hundred years ago, when personal correspondence was conducted largely in a “fair hand”. Originally, the recipient paid the postal fees when a letter was sent. Though this changed with the advent of the postage stamp, paper and postage were expensive commodities for many. Cursive proved a way to defray costs: people could write one page of cursive, turn the page 90 degrees, and then continue writing their letter on the same page. Cross writing would not have been possible with block manuscript.

In 1764, John Hancock inherited his uncle Thomas’ business and estate and became one of the wealthiest men in the colonies. As tensions between colonists and Great Britain increased in the 1760s, Hancock used his wealth to support the colonial cause.

But in a world in which everything from personal correspondence to job applications are chiefly computerized, the need for such a skill isn’t as pressing. Many school districts have abandoned cursive in favor of teaching basic computer literacy skills, a move which, in the eyes of many, better prepares kids for life in the technologically competitive 21st century. Teaching cursive as a discrete skill takes time away from teaching students how to communicate meaningfully, they argue. Admittedly, research that rationalizes cursive as an integral part of elementary curriculum is slim, and studies as early as 1966 were already calling it a redundant “tradition”.

Indiana Drops Handwriting from School Curriculum: Educators say other skills are more important in digital age

Indiana’s public schools are abandoning teaching children how to write in favor of showing them how to type. The state is among 48 others transitioning to new national learning guides, the Common Core State Standard Initiatives, that no longer require children to learn cursive handwriting but expected them to achieve proficiency with a keyboard.

An Indiana Department of Education memo said teachers can still choose to teach cursive writing, or can stop altogether. “State standards themselves, they’re just supposed to be a guide for what students must know before moving on to the next grade,” said department spokeswoman Stephanie Sample. “And there are lots of little details that aren’t in those standards that kids learn.”

Sample said she has not heard any feedback from parents who are concerned their children will no longer learn a basic, yet fading, skill.

How often does one write in cursive every day?

Much of our daily personal and business correspondence is done by a quick email or text message. Note-taking and composing essays or statements are done almost entirely on the computer. “There are much more important skills I think they take into this century than whether or not they write cursively,” said former Indian teacher Mark Shoup, listing critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork and literacy.

Scott Hamilton, an Indiana clinical psychologist, said it made sense to only teach children how to sign their names. “The time allocated for cursive instruction could then be devoted to learning keyboarding and typing skills. From an intuitive standpoint, this makes sense, based on the increasingly digital world into which this generation of children is growing up.”

When you read this character “hon,” it is a book. When you read it “moto,” it is origin.

Perry Klein, a professor of literacy education at the University of Western Ontario, said a child’s ability to compose depends on whether she can form letters clearly and accurately. “If students can form letters fluently, then that frees up their attention to focus on the content and language of what they’re writing,” Klein said.

Research has yet to be published, he said, on whether forming those letters works best on a page with a pen or on a computer screen. But as long as they can read what they compose, they will develop the right skills. “The important thing is that for kids to learn (printing) and cursive accurately and fluently, and if they have that, then they’ll be able to do written composition in a whole variety of situations,” Klein said.

The broader issue, said Andree Anderson, of the Indiana University urban teacher program, is not how students write, but what they write. “Students are carrying their texting into their daily writing, and that’s not something we want to see. We’re seeing acronyms in their writing and that’s not acceptable.”

The Case for Cursive

But there may be something to be said for keeping cursive. Studies have shown a grader bias against papers with messy handwriting, even though their content may be the same as those written neatly. The upswoop and italics of cursive teach fine motor skills, proponents say. Zaner-Bloser, a publisher of writing, vocabulary, spelling and handwriting programs, stands behind the method so firmly that they sponsor an annual handwriting contest. “Learners who become independent and fluent in writing manuscript and cursive letters enter a world of endless opportunities,” their Handwriting Within the Context of Literacy research review boasts.

Ethna Reid of Reid School in Salt Lake City would agree—her school almost swept the Zaner-Bloser competition at every grade level. Reid cites the impersonality of text messaging and other computerized forms of communication as a reason to teach the penmanship on which her school prides itself. Could abandoning cursive render us unable to read it in the future? Older generations, many of whom save heirloom handwritten documents for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, worry that this may be the case.

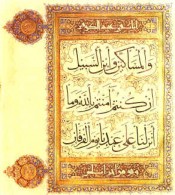

Old Persian Calligraphy

There’s no doubt that teaching good, legible handwriting skills, whether through print or cursive, improves kids’ ability to construct and convey thought. Still, the prevailing view is that teaching cursive in addition to print distracts schools from that larger goal. This opinion would come as no surprise to Randall R. Wallace, who heard cursive’s death knell over ten years ago. In his article “Simplifying Handwriting Instruction for the 21st century”, he writes, “It is evident that teaching two forms of handwriting has outlived its functional value in society and takes up space in a curriculum that is clearly overcrowded.” With Microsoft Word dotting i-s and crossing t-s for us, John Hancock’s John Hancock may be a relic of the ages.

This article was prepared from two articles that Merry Gordon wrote. “From Cursive to Cursor” appeared on Education.com and “Indiana Drops Handwriting from School Curriculum: Educators say other skills are more important in digital age” which appeared in the Vancouver Sun in July 2011.

Flexible preparation for your new grade

Flexible preparation for your new grade Preparing Teachers for 2024-25 Grades 1-8

Preparing Teachers for 2024-25 Grades 1-8 Bay Area Teacher Training

Bay Area Teacher Training Immersive Academics and Arts

Immersive Academics and Arts Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops

Jamie York Books, Resources, Workshops Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum

Waldorf-inspired Homeschool Curriculum Full-Time Teacher Education

Full-Time Teacher Education Waldorf Stories for Everyone

Waldorf Stories for Everyone Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli

Middle School Science With Roberto Trostli Space speaks. Its language is movement.

Space speaks. Its language is movement. Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime

Bringing Love to Learning for a Lifetime Enliven Your Teaching!

Enliven Your Teaching! Grade Level Training in Southern California

Grade Level Training in Southern California Quality Education in the Heartland

Quality Education in the Heartland Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips

Summer Programs - Culminating Class Trips Association for a Healing Education

Association for a Healing Education ~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~

~ Ensoul Your World With Color ~ Training in Traumatology & Artistic Therapies

Training in Traumatology & Artistic Therapies Caring for All Stages of Life

Caring for All Stages of Life Transforming Voices Worldwide

Transforming Voices Worldwide Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families

Great books for Waldorf Teachers & Families Waldorf Training in Australia

Waldorf Training in Australia Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses

Roadmap to Literacy Books & Courses The Journey is Everything

The Journey is Everything Grade-specific web courses for teachers

Grade-specific web courses for teachers Everything a Teacher Needs

Everything a Teacher Needs Train to Teach in Seattle

Train to Teach in Seattle RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds